Robert Adams and New Topographics

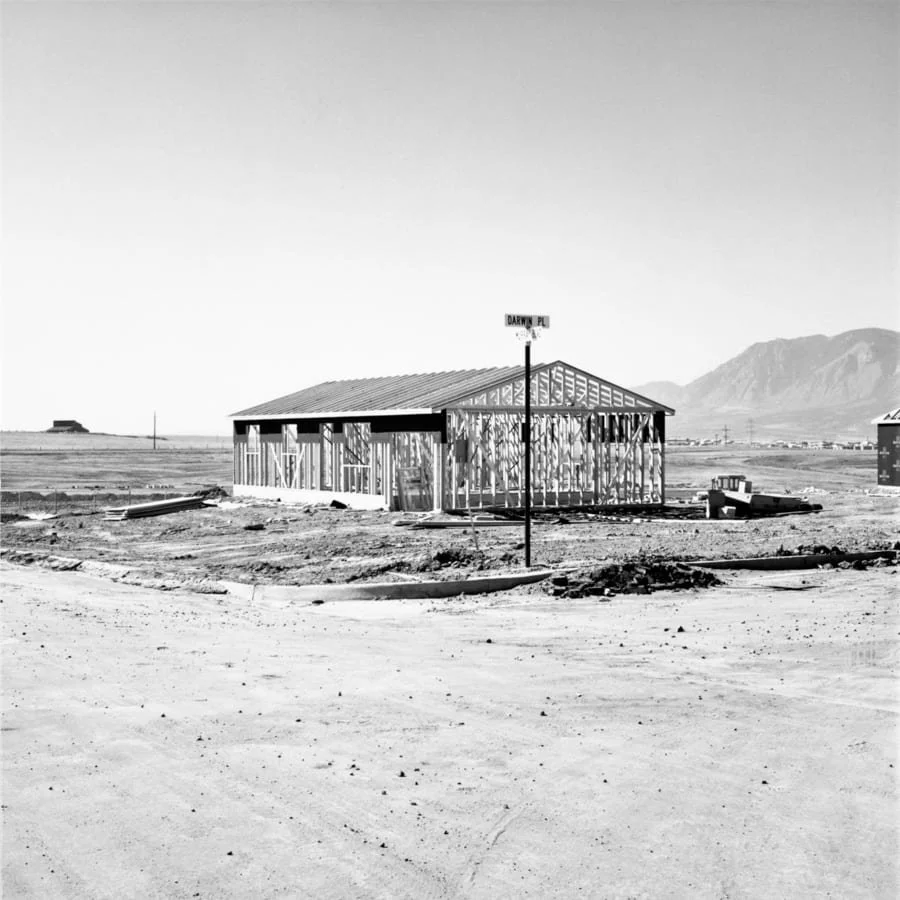

Robert Adams is a ubiquitous name in contemporary photographic circles, and for good reason. Adams’ work in the 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was part of a seminal moment in the trajectory of contemporary landscape photography. His photographs of a transformed and transforming Colorado front range in works like The New West have been seared in to our collective consciousness as Adams grappled with the ecological and existential implications of the sprawling suburban development of the Colorado landscape. The work of Robert Adams and others in the 1975 exhibition transformed the subject matter of the landscape photographer by supplanting the romantic ideal of nature with the more uncomfortable, less idealistic realities of the land in contemporary existence. The earth becomes historic for the first time with the new topographic photographers. In place of the 18th century romantic fantasy of nature we are confronted with the stark cost of modernity.

We all know this story, and in some regards we have become jaded by the ubiquity of the aesthetic legacy of the “event” of Robert Adams. But this is also not the whole story of Robert Adams, nor even the most interesting part, in my admittedly peripheral opinion. I don’t wish to diminish the importance of his early work in any way, but I do wish to point to a somewhat subterranean current in his body of work that only seems to become thematized for its own sake in the later years of his work.

Robert Adams | The New West

Whispering Sublime

Adams is quoted as saying at one point, “I thought I was taking pictures of things that I hated. But there was something about these pictures. They were unexpectedly, disconcertingly glorious.”

Adams was clearly dismayed at what he saw as the needless violence being perpetrated against the landscape and part of this does come through in the images. The photographs, especially those in the 1970’s, are not “easy viewing.” My first experience with Adams’ work was not a positive one. I could find nothing to affirm in it. I think that part of what makes it difficult for Adams’ work to hit for some people is that the photographs present us with a reality from which we rightly recoil. The juxtaposition of sprawling, banal urbanity with the tarnished beauty of the landscape confronts us with uncomfortable realities that call forward deep reflections about the meaning of the land and of our sojourn on it.

But even in what we might call the peak New Topographics phase of the 1970’s there is this quiet sublimity that whispers through the broken fragments of the land toward which Adams pointed his camera. This is what, I think, Adams points to as the “disconcertingly glorious” aspect. Beyond the sprawling tract homes we often see the silhouetted peaks of the Colorado front range, we are shown the open play of light, or we are shown a lone patch of scrub brush obstinately growing in the concrete bank of a highway. This is the quiet hope of Robert Adams, the delicate sublime that persists despite our worst failures, and it comes to occupy a more and more central place throughout the wandering pathways of Robert Adams’ photographic career.

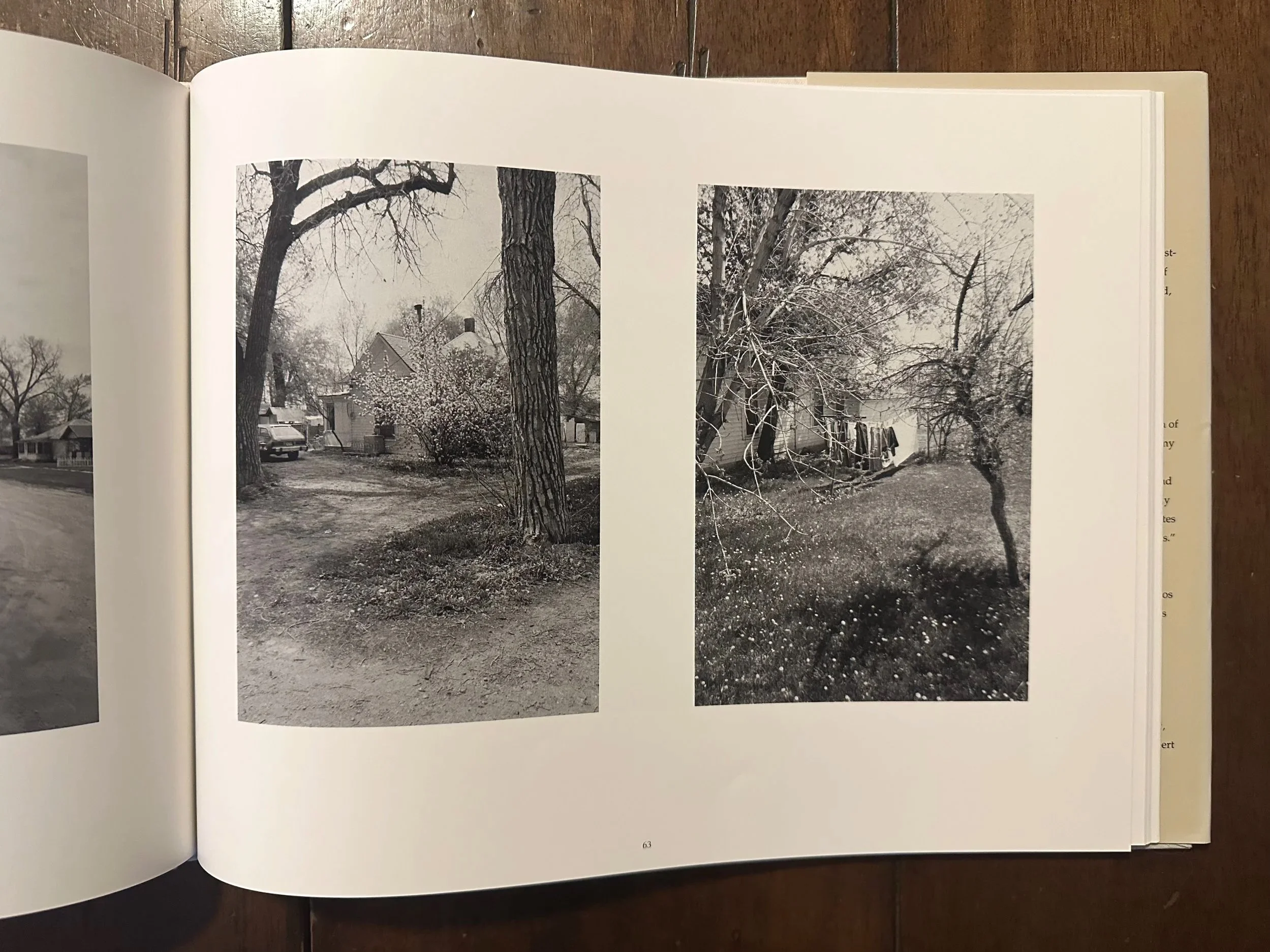

Robert Adams | From the Missouri West

Throughout the work of the 1980’s and beyond we see Adams increasingly pointing his camera toward that which he wishes to affirm rather than what he seeks to negate. For example his 1980 work From the Missouri West feels more like a love letter to the deep beauty of the West than the work from the 1970’s. Throughout his oeuvre we still find the characteristic juxtaposition of the “sacred” and the “profane” that makes Robert Adams’ work interesting but especially in his later life we find this increasing focus on the sublime, the beautiful, the numinous, etc.. I would perhaps feel more uneasy about attributing these notions to Adams’ work if it weren’t for the fact that he commonly uses this kind of language in his written works.

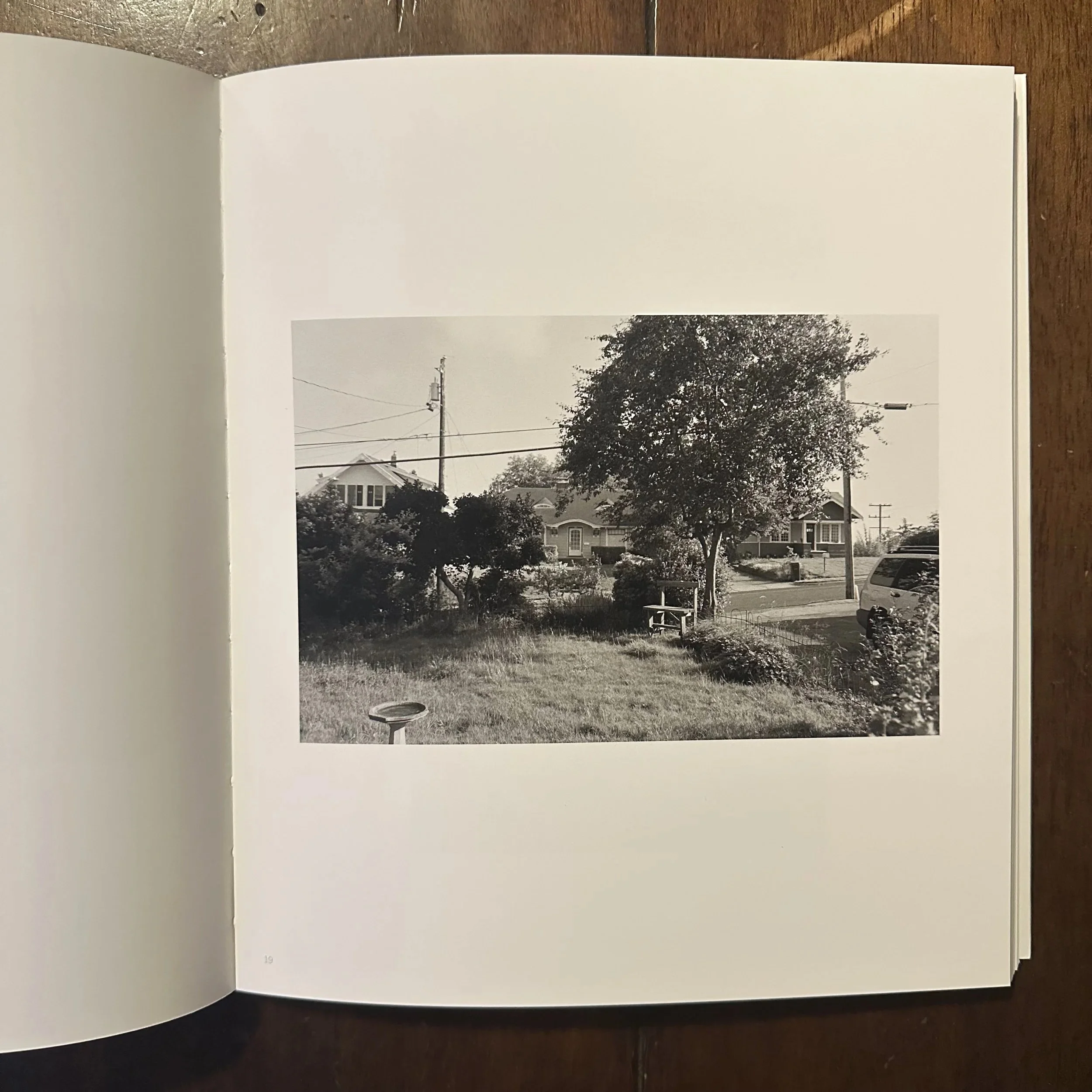

If I had to give a more concrete time period for this transition, the 1990’s seem to be important. This is when Adams starts working on West from the Columbia, which feels even more strongly like a devotional to the beauty of the land than the earlier From the Missouri West. A number of other book releases in the 1990’s also seem to make a thematic shift. Works like Cottonwoods, Listening to the River (my personal favorite) seem to show us a different sensibility at work in Adams, trading an unsettled tension of the human and the natural for hopeful affirmations of the sublime. Even a 1999 republication of some of his earlier work titled Eden seems to recast the work of the 1970’s in a way that gives more attention to the presence of the numinous shimmering beneath the surface of everyday life. And as we see Adams work progressing in to the 2000’s this focus only seems to deepen.

If pushed I would probably make the stronger claim that these experiences were always a motivating factor for Adams’ work. Why photograph sprawling tract houses in anger if not because of some sense that they were worthy of negation? Adams’ early work feels like it comes from out of this quiet reverence, a cry against the desecration of the beautiful. From the safety of disinterested speculation, and to use Adams (a la Why People Photograph) against himself, we might say that the turn in his work over the years is his attempt to find for himself that which is worthy of affirming in this life. Negation can get us far but it gives us nothing to live for. The beautiful, the sublime, the numinous. These are experiences of meaning, of purpose which transcends the mundane. In the words of the American poet Robinson Jeffers, “The beauty of things means virtue and value in them…It is the human mind’s translation of the transhuman intrinsic glory. It means that the world is sound, whatever the sick microbe does. But he too is part of it.”

Robert Adams | Pine Valley

The Photograph as Devotional

In Adams’ 1981 book Beauty in Photography we find, in the eponymous essay, an allusion to the idea that the function of art is to give witness to beauty. As he writes in that piece: “William Carlos Williams said that poets write for a single reason - to give witness to splendor (a word also used by Thomas Aquinas in defining the beautiful). It is a useful word, especially for a photographer, because it implies light - light of overwhelming intensity. The Form toward which art points is of an incontrovertible brilliance, but it is also far too intense to examine directly. We are compelled to understand Form by its fragmentary reflection in the daily objects around us; art will never fully define light.”

This dimension of Adams’ work was first illuminated for me when a friend recommended Adams’ 2011 work, This Day. The work in This Day consists of quiet everyday moments around Adams’ home as well as natural landscapes around the Northwest Coast. There is an opening quote in this book, printed in a soft gray text against the white pages which reads, “The category of the sublime is so vulnerable, so fragile—but it is, for all that, our final outpost…” The language of the sublime gives away (or maybe situates the viewer with the proper frame of reference), yet again, that the book is best understood as a practice of bearing witness to the sublime in daily life, with all the existential depth that that experience calls forward in us. Dappled light through an open window, or the play of light over grasses lain before the expanse of the Pacific Ocean are reflections on the presence of that quiet, meaningful beauty which Adams has hinted at in so many ways in so many places over the years.

Robert Adams | This Day

I said at the very beginning of this that I did not in any way intend to detract from Adams’ earlier work. A friend of mine pointed out in conversation the other day that the scope and depth of Adams’ influence some 50 years later only speaks to the prescience of his observations in the 1970’s. And understood in the proper context Adams’ earlier work is an important part of a larger conversation about ethical reflection on the relationship between humans beings and the natural world. But for all this hefty importance I can’t help but find a much deeper resonance with the work that would only come to full fruition some 20-30 years later. Someone could make the argument that I’m simply jaded, and not giving the earlier work its due reverence. You know, the way someone who lives in a world already influenced by Led Zeppelin might struggle to understand how impactful the band was. Maybe, and maybe Stairway to Heaven just kinda sucks. In My Time of Dying is a better song, but now we’re on a tangent.

To get back on track, the quiet hope in the late Robert Adams is the experience of grace. It is the direction of our gaze toward the beautiful. In an age of nihilism and disenchantment, and amidst the pains and turmoils of our worldly existence, it is the subtle reminder of that quietly shimmering beauty which is the foundation of the world and which remains an inexhaustible, eternal possibility. In the words of the American writer Wendell Berry, is it that vision by which we “…see that the life of this place is always emerging beyond expectation or prediction or typicality, that it is unique, given to the world minute by minute, only once, never to be repeated. And this is when I see that this life is a miracle, absolutely worth having, absolutely worth saving. We are alive within mystery, by miracle.”

This is the beautiful, subterranean current of Robert Adams that I have come to enjoy so much and which I wanted to share with you.

Robert Adams | Listening to the River

Also, as an addendum: Seriously, find a copy of Listening to the River. It’s such a beautiful book and maybe my favorite Robert Adams book.