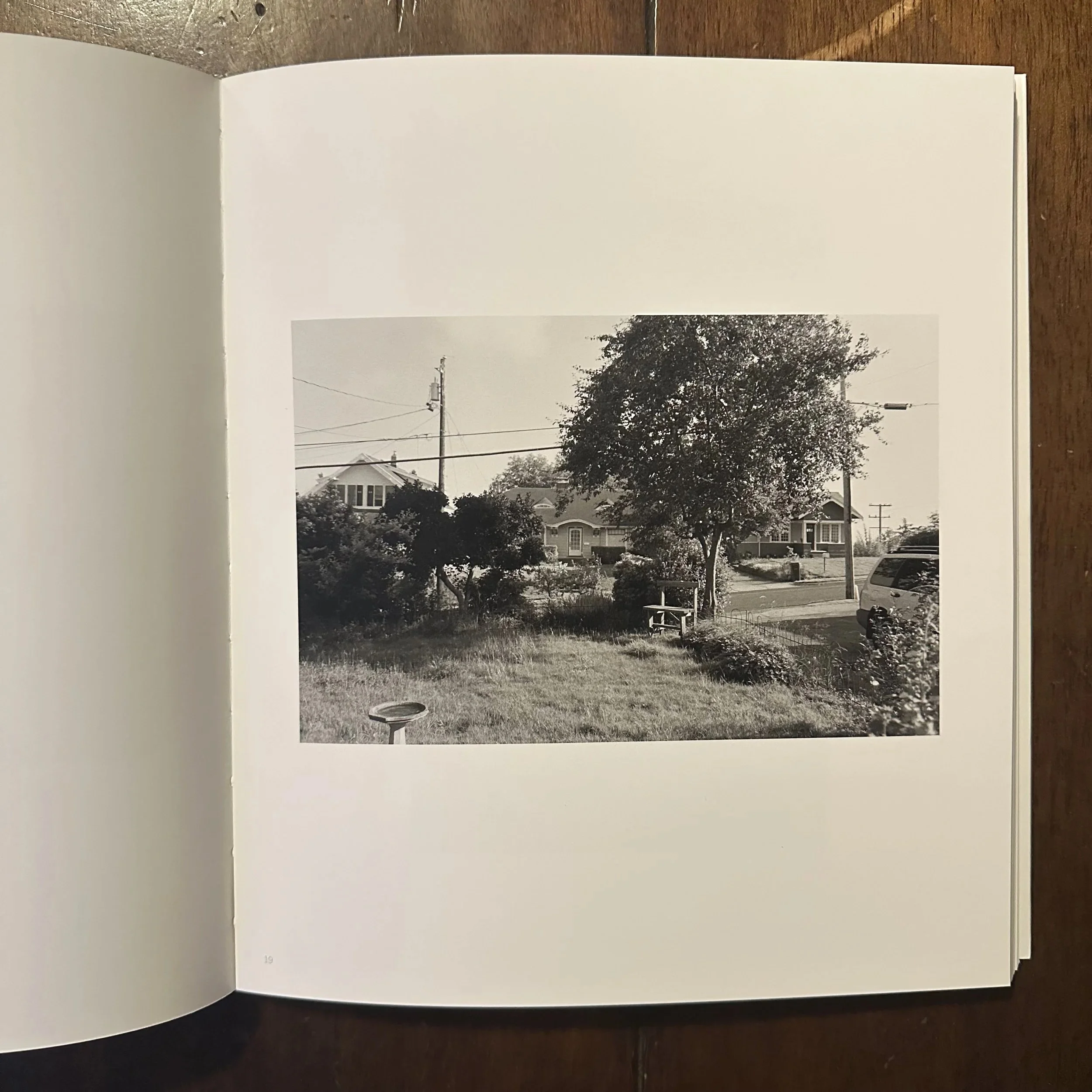

Autumn strolling and shade

Leica M262 + Leica Elmar 50/2.8

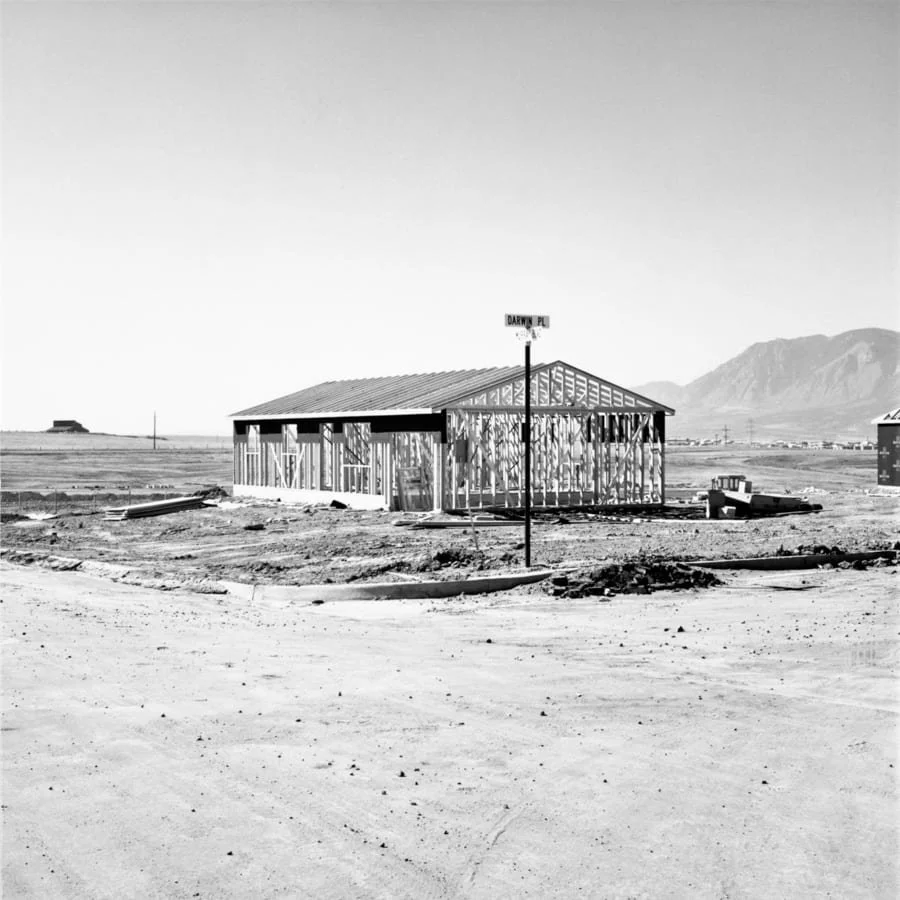

I just published that piece on Robert Adams a couple days ago and it felt weird to spend last night without writing something on the laptop. If you haven’t read that, check it out. Some people have called it better than the schizophrenic drivel that Tim Carpenter vomited on the pages of that one book about dying. Anyways, we took a walk this morning around the neighborhood before the sun got too high.

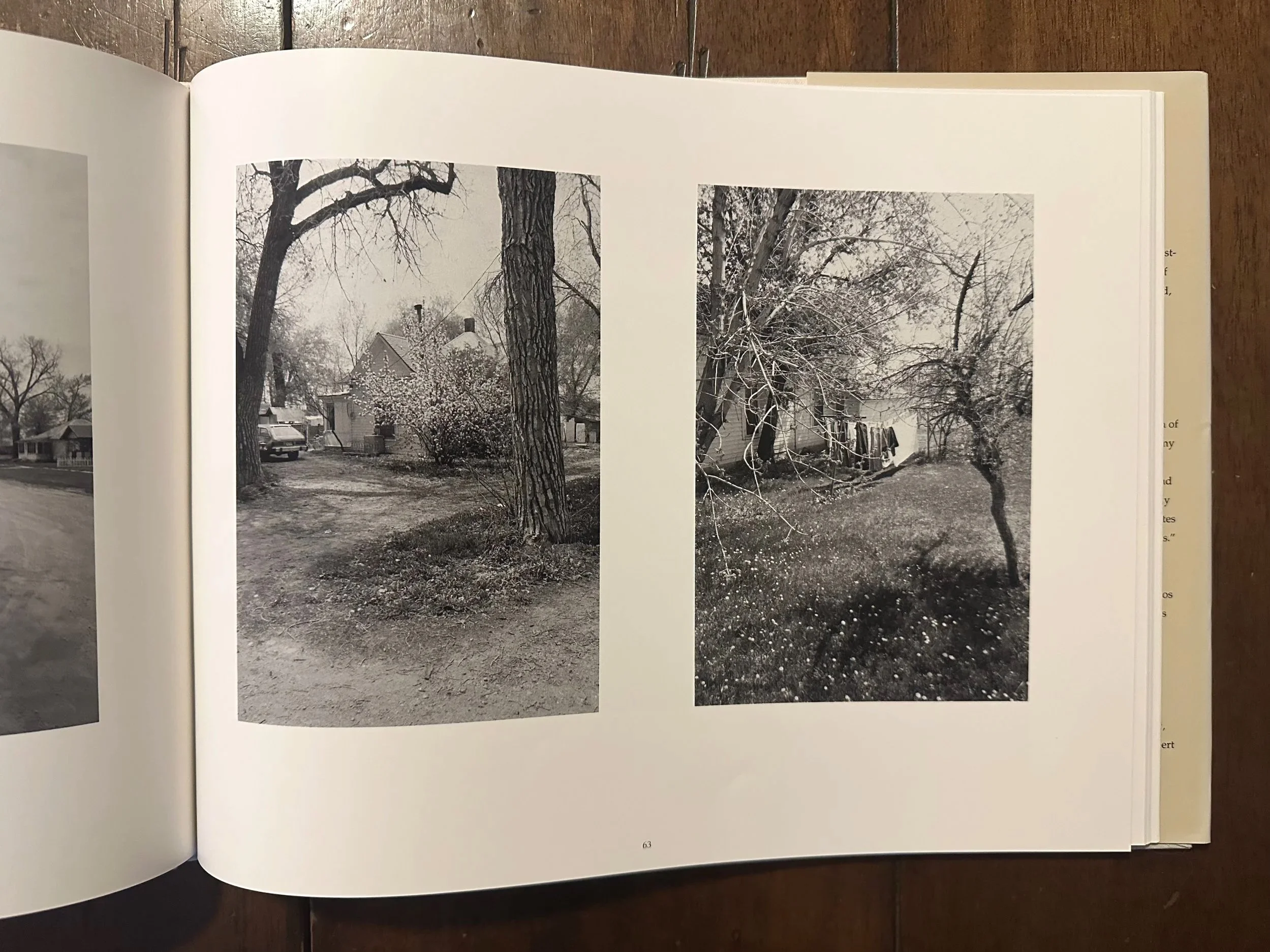

I took the Leica and the Elmar to test out the 6 dollar lens hood I got for it to try and tame some of its tendency to flare. Leica makes a dedicated hood for the Elmar-M that looks really slick in a matching silver but FFS it’s $150 USED on the eBays, so, uh, I’ll take the cheap Amazon lens hood. It worked pretty well, only flaring in a few minor circumstances. I hate lens flare, to be honest. One of the things I do love about my Zeiss Planar is that I can shoot it like an absolute idiot and it can handle just about anything with very little fuss. It’s a great lens to throw on the front of the camera and forget about. But, the Leica does render in a somewhat more pleasing manner.

This was about the worst flare

Jess walking, but also, no flare shooting toward the sun

The Elmar tends to render a little softer than the Planar. It’s still wildly sharp, especially considering it was made something like 50-60 years ago. This copy has had the benefit of a CLA from Youxin Ye as well which helps it feel as good as it probably did when it left the factory all those years ago in Germany. But, it has a kind of “organic sharpness” if that makes any sense. It’s sharp without being clinical or crunchy. It has a balanced contrast to it as well, unlike some modern lenses which can tend to have kind of insane micro-contrast. It gives the appearance of sharpness but at the cost off a rendering that to my eye can feel harsh and unnatural.

That’s about it from me. I’m going to go back to enjoying my freedom from writing in the evening. I’ve been working through some of Charles Hartshorne’s work in process theology. Wish me luck.